A guest series by Fraser Pettigrew (aka our New Zealand correspondent)

#11: Teenage Kicks – The Undertones (1978)

Some records, like other iconic cultural artefacts, become so famous that they defy objective analysis and enter an indefinable zone of existence divorced from history and context. They become Mona Lisas, Beethoven’s Fifths, Venuses de Milo. They are talked about so much for so long that they seem impossible to discuss without retreading paths worn into deep ruts through constant repetition.

Thus, with Teenage Kicks, as with Spiral Scratch, I find myself boldly going where literally thousands have gone before me. One cannot proceed without mention of John Peel and his epitaph, nor can one even think the words “teenage kicks” without hearing those three chords, eternally descending and ascending and inverting.

And yet, simply by undertaking this hopeless task as part of a series on EPs, it occurred to me that the thing Teenage Kicks is least famous for is being but one of four songs on The Undertones’ first release. The iconic one has taken on a life of its own, floating magically alone in the ether of consciousness, while True Confessions, Smarter Than U and Emergency Cases languish in semi-darkness, like the other two Walker Brothers, Thingmy and Whatsisname.

True Confessions at least made it onto The Undertones’ first LP. It’s such an infectious number that you wonder whether Terri Hooley ever got to play it to any of the record execs in London when he went hawking Teenage Kicks to the big labels, or if they threw him out straight after telling him the lead song was the worst thing they’d ever heard. Surely if they’d heard True Confessions as well, they might have changed their tune?

The other two songs are none too shabby either. They give due warning of the seemingly inexhaustible production line of catchy tunes that John O’Neill would deliver over the next half-decade, ably supplemented by brother Damien, and band members Michael Bradley and Billy Doherty. Altogether the disc is a perfect little sampler of what was to come, and if the title track hadn’t taken off as it did, the disc would surely now be remembered much more as a classic EP of the era.

John O’Neill, of course, has always been modest to the point of disparaging about Teenage Kicks as a song. He felt it was a bit derivative and not particularly clever, just the product of following a similar route to The Ramones in turning old 60s Spector and surf style into 70s punk-powered pop. Sometimes it’s the simple things that work best, however, a sentiment that John Peel evidently agreed with.

You could point out that the other songs are hardly of symphonic sophistication. O’Neill’s diffidence towards his own work was partly down to the lyrics, provoking a slight embarrassment at the clichéd theme of Teenage Kicks. Brother Damien poked fun at it with his deliciously titled More Songs About Chocolate and Girls that opens second album Hypnotised, but John almost defensively has called that song “a bit twee”.

Clichéd is not a word you’d use of the other songs. The lyrics are quirky, sometimes cryptic, witty, but don’t labour a point beyond hanging on any hook provided by the music. “Each song makes its point and then ceases,” said Paul Morley in praise of the first album, a critic not notably averse to complicated things. All the tracks on the debut EP are of Morley-approved brevity, three of them qualifying for this blog’s Songs Under Two Minutes series (though only True Confessions has featured thus far). Teenage Kicks makes it 28 seconds into the third minute, probably only on account of the slower tempo.

In his memoir Teenage Kicks: My Life as an Undertone, bassist Michael Bradley revealed that Emergency Cases was basically the Rolling Stones’ Parachute Woman (from Beggar’s Banquet) played at hypersonic speed (perhaps the parachute failed to open). The band played the original as a blistering cover version before John O’Neill decided to make his own song out of it. “When we decided to upgrade it,” says Bradley, “John sped up the riff beyond recognition. That’s our defence if the ghost of Allen Klein ever sues.” All in the finest tradition of blues robbery, as practiced by many, including The Rolling Stones.

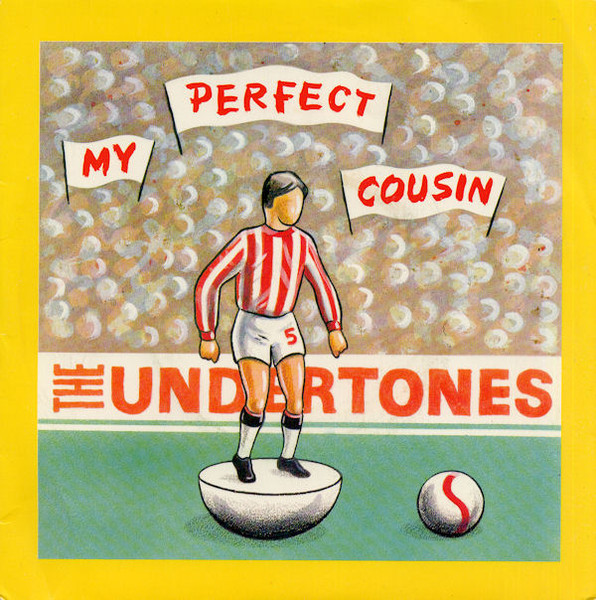

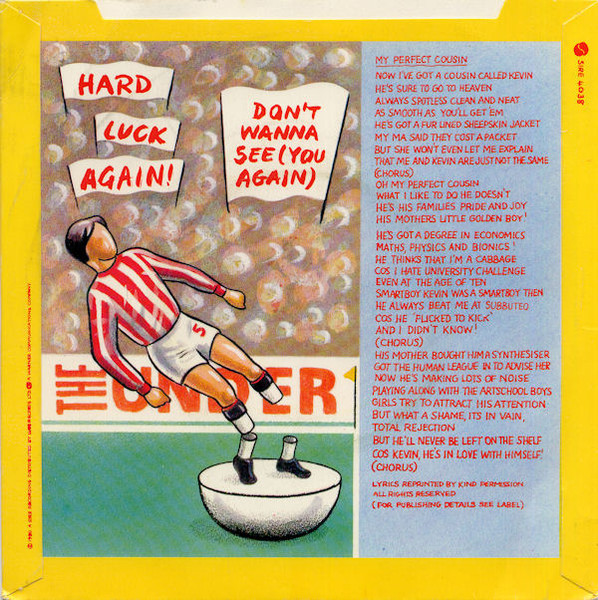

Peel’s patronage was undeniably crucial in the take-off trajectory of The Undertones, landing them the deal with Sire that brought the EP (also in two-track single format) to an audience that Hooley’s Good Vibrations label could never have reached. But judgement in the court of public opinion is just as important. Peel championed The Fall with comparable dedication, but the masses never took to them in quite the same way, for obvious reasons. (Their highest charting single came after ten years of effort and peaked one place higher than Teenage Kicks at 30, and that was with a Holland-Dozier-Holland cover!) The Undertones delighted a wide range of fans with their much more accessible charms, and if they had never committed another thing to record, this quartet of gems would surely have secured a corner of music history for them.

My copy of Teenage Kicks is the Sire release, bought in late 1978. It’s not clear exactly how many copies were ever pressed on the Good Vibrations label, but it can’t have been many, and there was barely one month between its initial release and its appearance on Sire in October 1978.