A DEBUT GUEST POSTING by FRASER PETTIGREW

There’s an archive clip in the unmissable new Sparks Brothers documentary that captures a moment of pure 1970s pop culture. During a live Sparks performance, sometime in 1974, the stage is being gradually invaded by the crowd, with security overwhelmed and unable to stem the tide. The band gamely strive to play on and at one point Russell Mael, with trademark energy, strides buoyantly across the stage belting out ‘This Town Ain’t Big Enough For the Both of Us’ only to be completely floored as he runs straight into an advancing phalanx of teenage girls.

YES! I thought, this is EXACTLY what gigs were like when I started going in the late 1970s! Pure uncontrolled mayhem! Hysteria and misbehaviour! Mob rule!

At some point many years later in my gig-going life I recall seeing kids literally queuing by the side of the stage during a performance, waiting to be ushered up and fed delicately onto the outstretched hands of the crowd, thence to ‘surf’ gently to the back, where they were deposited onto the floor like five year-olds on a boogie-board washing up in the shallows. Where, I asked myself, had it all gone wrong?

One of the first gigs I ever went to was The Clash at Edinburgh’s Odeon cinema in November 1978. From a balcony seat at my first gig, The Boomtown Rats a few months earlier, I had learned straight away that the place to be was down in the stalls, where a boiling mass of teenage ferment was seemingly connected by direct current to the frantic charge of ‘Looking After Number One’ and ‘Mary of the 4th Form’.

Accordingly for The Clash gig, my friends and I queued before the box office opened and secured stalls seats, quite far back, but wisely located on the aisle. When The Clash took the stage on the night we were well placed to bomb down the aisle into the explosion of human energy at the front just as the stage lights blazed and the band smashed into ‘Safe European Home’.

As I duly boiled in the teenage ferment I became aware that the row of seats into which I had insinuated myself was no longer fully attached to the floor and was moving back and forth with the surging crowd. Between me and the stage the fans were gleefully pogoing up and down on top of the remnants of the first half dozen rows of stalls, which must have succumbed within seconds to the rampaging punks.

Pretty soon my row of seats resigned itself to fate and capsized gracefully into the sea of legs in front of me. I was compressed in a bouncing, sweaty fug as The Clash continued their breakneck set. Had there been any rows left I would have been about three or four from the front, close enough to see the idiots who still seemed to think that gobbing was punk style in late 1978. Strummer was splattered by a steady stream of saliva that slithered down the body of his guitar, a translucent slime of pure stupidity.

During the encore The Clash attempted to play ‘White Riot’ but, Sparks-like, the stage quickly filled with fans, dodging the bouncers with side-steps worthy of a Welsh stand-off. Most of the song was smothered as people crowded around Strummer and Jones, making it impossible for them to play their guitars. Paul Simonon managed to escape onto the drum podium from where he and Topper Headon kept the bassline and rhythm going to guide the massed chorus of ‘White riot, I wanna riot, white riot, wanna riot of my own’, yelled tunelessly into the mikes by everyone on the stage. I saw someone grab a stand and inadvertently whack Strummer in the mouth with the mike. I wondered if that was the origin of his famously cracked incisor or if it had always been like that.

Bouncers vainly tried to throw people back into the crowd and intercept new interlopers. In the midst of it all Viv Albertine and Ari Up of support band The Slits skipped merrily from one side of the stage to the other, after the fashion of Eric Morecambe and Ernie Wise.

The recklessness of punk crowds was legendary in those days, matched only by the ferocity of bouncers. Some other friends who went through to Glasgow’s Apollo Theatre to see Siouxsie and the Banshees told me they saw one bouncer literally punch a fan in the face, knocking them right off the (rather high) stage. Had it not been for the packed crowd onto which they fell it might have ended more tragically, but then it wouldn’t have been the first time at a rock gig that the security turned out to be the biggest threat to people’s safety.

From subsequent gigs by The Jam and even Elvis Costello I realised that the seat-trashing thing was pretty much standard procedure. The theatres must have been creaming in so much profit that they could factor in the repairs to their break-even calculations, otherwise why the hell did they ever book bands?

And therein, my friends, lies the clue to the present age of sanitised, stage-managed, emasculated rock and roll. It’s a business – no shit Sherlock, it always was – but like every other sphere of business since the 1980s it’s been modernised, commodified and globalised until it’s just as much a part of everyday life as a Big Mac, an alco-pop, an iPhone and a pair of dropped-crotch jobby-catchers. ‘They got brand new suits – huh, you think it’s funny, turning rebellion into money,’ sang Joe Strummer that night in 1978. We thought it was a challenge, not a prophecy.

Which is not to say I’m pining for the days of uncontrolled violence at gigs. I know that if I was a parent now I’d be absolutely shitting myself at the thought of my kids going to events like that. My parents, coming from the generation before rock’n’roll, were blissfully ignorant of what I was up to, despite the media’s moral panic over punk rock.

The worst it got was when they picked me up after seeing The Rezillos at Clouds Ballroom in August 1978. Living out of town as we did, I could make a late bus home after a gig at the Odeon, but I knew shows at Clouds were a different matter. My parents agreed to pick me up when I told them disingenuously that it would likely finish ‘about 11 or 11.30’. When I finally emerged at 1.30am they were far from amused, not least from having sat for two hours watching the human debris floating around Tollcross at that time of night and the state of Edinburgh’s punk proletariat disgorging from the ballroom alongside me.

Thankfully the gig was well worth it. The memory of a wee boy, no more than 10, extricated from the molten crush at the front, riding piggy-back on lead singer Fay Fife while squirting the crowd with a water pistol will never be erased, least of all for that kid, I hope.

At a couple of points in The Sparks Brothers film, reference to the Mael’s early captivation by rock’n’roll is visualised by the same black and white footage of wrecked theatre chairs being aggressively thrown into a pile at some 1950s Jerry Lee Lewis gig. The Killer pounds his piano while lines of nightstick-wielding police officers try to protect the stage from the riotous assembly before them. It’s a stock image of rock’n’roll carnage, its threat to order, its dangerous ability to induce frenzy in the young. The intention is ironic in Sparks’ case, but still, you get my point. Those chairs.

From its emergence as a truly mass popular music genre, rock’n’roll was barely much more than 20 years old by the time I started going to gigs, and the punk revolution had reinvigorated its disruptive, rebellious character for my generation. Looking back now, more than 40 years after I trampled the Odeon’s seats underfoot, it almost seems as though that time was already rock’n’roll’s last fling as a spontaneous transformative force in cultural and social norms.

You might think I’m about to deliver some piercing cultural insight about rock’n’roll, globalised capitalism, social and cultural revolution, and the pivotal role of theatre seats in it all. Or maybe I’m just another old Gen-Xer, rolling out the nostalgia for the liberating moments of our adolescence. Wonderful in young life. It was a glorious experience. Kids today will never know, etc. And neither they will, but maybe they’ll know things we never can and music will change their lives in different ways to how our music changed us.

The truth is that between 1955 and 1985 our social world changed more than in almost any other 30 year period in peacetime history. Rock’n’roll was as much a symptom of that change as a cause, and we kid ourselves if we think it was the other way round. The mayhem of music’s performative rituals during those three decades was like the ground cracking and buckling in an earthquake. Social and intergenerational relations were being remade and it was a rough ride for a while.

But since the 1990s there has been little remaking to be done. Now the parents of teenagers are people who have grown up through those social changes themselves. They’re not the monolithic conservative and conformist generation born before the war, before rock’n’roll. They accept the end of deference, the notion of social mobility, the reality of sexual liberation. They don’t really care whether people are gay, or unmarried mothers, or wear their hair long, or smoke a bit of dope now and then. Those things don’t threaten anything in their lives anymore. They’re people like me, who went to Clash gigs when they were 15.

The revolution is over. It’s been televised, and you can watch it all again on those decade nostalgia programmes produced by Tom Hanks. There is no wild rock’n’roll mayhem anymore because there’s no need. There are still revolutions to be had, but they’re not of the kind that pitted kids against their parents. Rock’n’roll is just music now. So you can stop, flip down the cinema seat and sit quietly watching for the rest of your life, and if you live long enough the ground will start to shake again.

FRASER P

JC adds…….

First of all, a huge thanks to Fraser for a wonderfully written debut piece for the blog. I really hope it’s the first of many, and again I realise just how lucky I am to have so many talented folk out there so willing to give freely of their time.

Secondly…..I’ll echo Fraser’s words on the Sparks documentary. I had prepared a review of it, having gone along to see it on 30 July when it was followed by a Q&A with the Brothers Mael, hosted by Pete Paphides, but I pulled it when I saw that Fraser had opened up his piece with a reference to it. If it is still playing in a cinema near you, then I’d recommend you get yourself along.

Thirdly…the incident at the Glasgow Apollo mentioned by Fraser was quite rare, for the simple fact that the stage there was at least 15 feet, which meant you couldn’t clamber up from the stalls and it would take a death-defying leap from the balcony to reach your idols….but it did, occasionally happen, most likely thanks to a combination of booze and speed making the bloke (and it was always a bloke) thinking he was Superman.

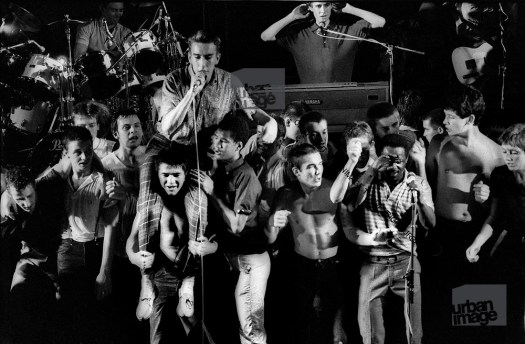

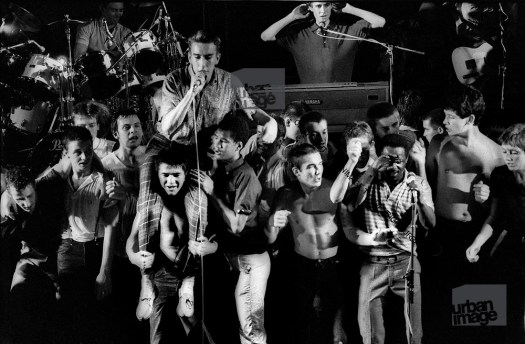

Fourthly….I couldn’t find a good or clear photo of any invasions at punk gigs, and the one use above is from the Specials playing in Brighton in 1979. It’s maybe a bit more friendly and less confrontational than the punk invasions of the era, but it certainly captures the chaos.

Finally….Fraser didn’t offer up any music to go with his words, so I’ve picked out a few based on what he’s written:-

mp3: Sparks – This Town Ain’t Big Enough For Both Of Us

mp3: Boomtown Rats – Mary of The 4th Form

mp3: The Clash – White Riot

Again, huge thanks to you, Fraser. Keep ’em coming.