A guest posting by Chaval

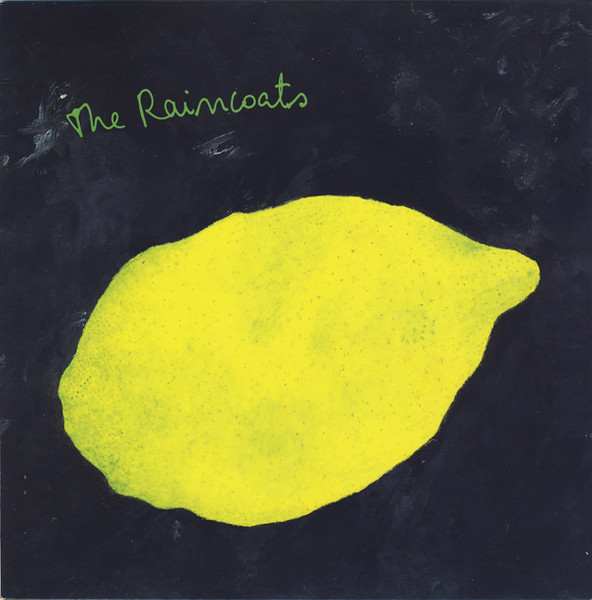

One of the last shows I saw before Covid lockdown put an end to live music for a couple of years was a low-key affair in a cool little theatre in Hackney. It was November 2019 and The Raincoats had reconvened to celebrate the 40th anniversary of their debut album.

It was a warm and nostalgic night, with an audience that seemed predominantly made up of survivors of the late 70s West London squat scene that had created a richly creative post-punk music environment. When the Raincoats introduced an old friend from back in the day to provide a short support set in the interval, it turned out to be Green of Scritti Politti (playing the hits).

The founding members of The Raincoats were Portuguese singer and guitarist Ana da Silva and English singer and bass player Gina Birch, Hornsey Art School teens who met in 1977. They were joined in 1979 by Vicky Aspinall whose distinctive violin-playing became a key element of their unique sound.

Their own set that night at Hackney was a reminder of the strange beauty of their music, mesmerising rhythms meshing with abrasive guitar, vocals that combined harsh atonality with melodic grace, sometimes in a single chorus, and visceral, emotive lyrics tackling some unsettling subject matter.

Kurt Cobain famously adored The Raincoats, although it’s difficult to see much musical common ground with Nirvana, and actually a bit irritating to think that such an original and distinctive band need any validation from a US rock star. Man had taste though. (Even with his endorsement, their profile remains low-key. If you Google the band, be prepared to wade through a lot of ads offering outdoor wear for the wet season).

Theirs is a music that traces a willingness to challenge the parameters of post-punk, that anticipated the “world music” trend, is of its time and timeless. Their first three albums, The Raincoats, Odyshape and Moving, were each very different works, singularly compelling. They reformed to make another record in 1996, but it was not in the same league, and does not feature here. Gina Birch’s solo work and her Hangovers project were OK, but still not comparable to the mercurial genius of the Raincoats.

OK, just want to say, let’s have some music now, yeah?

Let’s start with a tester, first track, debut album. Haphazard bleeps, clicks, squeaks, meandering bass, scratchy violin, a bit of sax, sighing, harmonic chant vocals – all the Raincoats’ bizarre appeal wrapped up in a squally melody in one minute 46. It gets easier.

The title of this 1982 single b-side might promise strident feminism, but it’s not quite that, more a beautiful assertion of the new gender realities delivered over an enchantingly elegant bass and percussion line. The rhythmic inventiveness and gentle but provocative vocal offer a kind of arch riposte to Scritti’s ‘Sweetest Girl’ from the previous year. What’s the feminist word for ‘masterpiece’?

From Odyshape, the Raincoats’ second and most out-there experimental LP. This song is built around a startling combination of drone guitar and kalimba (an African thumb piano – me neither) embellished with a mesmeric clockwork rhythm that seems borrowed from the soundtrack of an intense European psychological thriller. Da Silva’s sinuous vocal keeps things unsettling.

There was a lot of soft jazz pop around in 1982, and this cover of the Sly and The Family Stone track was as close as The Raincoats got to mainstream (number 47 in the charts, apparently). Again the clattery percussion sets it on a path away from pop smoothness, although the trumpet keeps dragging it back with that blissful melody.

A standout from the debut LP. Now I always thought the chorus to this was “in love is so fucked up”, but the written lyric suggests “in love is so tough on my emotions”. Seriously? The lurching, anguished, exhausted vocal supports my thesis. With atonal guitar and Cale-Velvets style violent violin, this is the most harshly realist love song ever, brutally honest about the debilitating and alarming effects of romantic obsession. The last minute is gloriously horrible.

The full 12” version on the B-side of the Animal Rhapsody single from 1983 blends another one of those off-kilter rhythms with fluid African guitar. There is an enchanting mish-mash of female and male vocals and a lyric that draws on Levi-Strauss’s work on women in primitive societies occupying a borderland between culture and nature. A Rough Trade recording contract came with a library ticket in those days.

The opening track on Odyshape has a subtle, whispered intimacy at odds with its title, starting off sedate, becoming anguished and desperate with a lyric awash with paranoia, vulnerability and anxiety The percussion, nagging rhythm and tension on the two minute coda to this track are astoundingly effective.

Yes, the worse song title ever, but the first track from the Moving LP is partly a loping singalong, with an inviting bassline, sax stabs and a chorus chant of those title noises that occasionally suggests an alternative universe Bananarama. Except great, obviously.

From the Odyshape LP, this is a stream of consciousness expressing random domestic anxiety (the lyric was written by Caroline Scott) where the disjointed rhythmic swerve of the music and murmured vocal are at odds, summoning up a disturbing, edgy atmosphere. The title is fooling nobody.

Yes, that Kinks song of gender confusion and cherry cola. The vocal manages to be both strident and vulnerable, and the levels of gender fluidity take on extra complexity with a female vocal masquerading as a male encountering a male masquerading as a female . . . A 60s cover that was ahead of its time, paradoxically.

chaval

JC adds………………..

chaval put this piece together more than six months ago, but for some reason or other it never reached the TVV inbox, but he assumed I’d decided not to run with it for some spurious reason or other. It was only after reading Fraser‘s recent piece on an EP by The Raincoats that chaval got in touch to ask after the missing/unpublished ICA.

I just want to take the opportunity to thank chaval for his patience while, between us, we sorted things out…..and to also remind everyone that I never turn down guest offerings; so if you’ve ever submitted something that hasn’t appeared, then please get back in touch, and you should hear back from me within a few days or so. (allow a week!!!!).

It might be the case (as it was with chaval) that the emails aren’t getting through to the TVV hotmail address for some strange reason or other, in which instance, leave a comment behind at a relevant post, and I’ll pick things up from there.

Cheers.