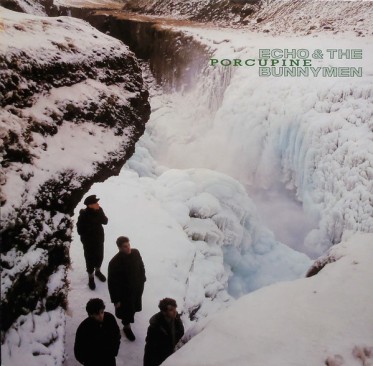

Album: Porcupine – Echo & The Bunnymen

Review: NME, 22 January 1983

Author: Barney Hoskyns

Perhaps it was inevitable, even decreed in some heaven up “there”. Maybe it’s just the third time unlucky. But if Porcupine isn’t good it isn’t because it lets you down. It fails, aggressively and bitterly it fails.

Porcupine is the distressing occasion of an important and exciting rock group becoming ensnared by its own strongest points, a dynamic force striving fruitlessly to escape the brilliant track that trails behind it.

Out of confusion or compulsion, the Bunnymen in Porcupine are turning on their own greatest “hits” and savaging them. In the name of what – pain? doubt? – Heaven Up Here said Yes We Have No Dark Things; now every former whisper of sickness returns in full volume. What one hears is a group which cannot flee its own echo. Porcupine is obviously deficient in vital unquantifiables but it’s just as obviously obsessive in its refusal of them. One feels it is the painful struggle to begin anew – and not from ashes either – that has determined the profound stasis, the agonising frustration of this record.

From the very beginning, the single ‘The Cutter’, Porcupine uses all the group’s key hooks, all the inimitable beats and bridges of ‘Crocodiles’ and ‘Heaven’, but ruthlessly strips them of the fervour that has so often bristled this reviewer’s quills. For starters, commercially ‘The Cutter’ isn’t so much as lined up for the TOTP race. Apart from an exaggeratedly Bowiesque bridge passage – a pastiche of ‘Heroes’ – the song (which may or may not be concerned with death’s scythe) is hopelessly lacking in the poppy intensity of ‘The Back Of Love’. And aside from the sitar introduction (which like the Bowie interlude crops up again in ‘Heads Will Roll’) the sound is striking only in its ordinariness.

Most people would have taken the chords of ‘The Back Of Love’ at half the speed the Bunnymen do. I thought it one of 1982’s best crude blowouts but it has little to do with Porcupine and sticks out almost obtrusively as an isolated moment of affirmation. From thereon-in, the album is non-stop anxiety. The remaining eight songs are really one long staggered obsequy to Heaven Up Here.

To begin with, Ian McCulloch’s poetry has grown oppressively more vague and difficult, although (again) you wonder whether simpler musical frameworks might not have inspired simpler, more direct lyrics. I’d like to think ‘My White Devil’ was a song of obsession and cruelty, but its opening lines rather dampen one’s enthusiasm: “John Webster was one of the best there was/He was the author of two major tragedies…” Very succinctly put, but what the intention behind this bald statement is I haven’t the faintest clue. One great moment rears up out of the “mist of error” when the song’s sense of panic rises to a claustrophobic climax of overlapping voices only to fall back into the lifeless refrain it escaped, but this is not enough to salvage the song in one’s memory. If I could make out more of what McCulloch was singing I’d probably unearth a few extra burial metaphors from ‘The Duchess Of Malfior’ (sic).

‘Clay’ continues in the same vein, with another torture-chamber opening and a discordant clash between Mac’s diffident vocal and Sargeant’s guitar twisting below like a knife in the stomach. But as we hit lines like “When I fell apart, I wasn’t made of sand/When you came apart, clay crumbled in my hand”, or “oh isn’t it nice, when your heart is made out of ice?”, the Jacobean psychedelia gets a little heavy-handed.

It’s as though the group had denied itself the luxury of simplicity, of what they perhaps take to be some too transparent “power” of rock. The firmly grounded structures of ‘Show Of Strength’ and ‘With A Hip’ are subverted, undermined by melodies that, like Webster’s “ship in a black storm”, know not whither they go. This Echo is less upfront, shorn of its poise and confidence. Ian Broudie’s production introduces more background activity – more keyboard, more percussive embellishment; in place of synthesisers, warped, sliding strings recall The White Album or Their Satanic Majesties Request; grating, ghostly effects hearken back to Walter Carlos’s ‘Clockwork Orange’; guitars backfire as though in a fit. Yet while all these random contingencies are part of the same drive to transcend, they succeed only in calling attention to that drive’s failure: the songs themselves remain fundamentally dead.

Only on ‘Porcupine’ itself do the various strains of despair coalesce. A kind of ‘All My Colours’ on a bad trip, its final exhausted throes are as draining (and as moving) as the bleakest moments of ‘Hex Enduction Hour’ but devoid of The Fall’s humour: just a voice crying against nothing, a beat banging on into the void. As the sound fades into darkness, a slight voice claims to have “seen the light”.

“Missing the point of our mission” , sings McCulloch dolefully, “will we become misshapen?” – the somewhat forced alliteration aside, that is probably the most candidly revealing line on the record. But if the song ‘Porcupine’ is the most shockingly dispirited thing Echo And The Bunnymen have ever done, Side Two horrifies the more for its uniform lack of inspiration, for the fact that every number cops direct from earlier songs without preserving anything of their energy or invention. Traits such as Mac’s trick of singing a line in one octave and then repeating it in a higher one have become stale and predictable trademarks.

Webster’s worms may wriggle in the intestines of these songs but to the ear it is music which sounds destitute of first-hand feeling. ‘Heads Will Roll’ commences like a Mamas And Papas drug song before plunging like ‘The Cutter’ into an enervated echo of Bowie. “If we ever met in a private place” , sings Mac, referring perhaps to Andrew Marvell’s “fine and private place” (i.e. the grave), “I would stare you into the ground/That’s how I articulate…” So now you know. Another very probable lit. ref. lies in ‘Ripeness’ (Porcupine’s bloodletting of ‘A Promise’), this time to Keats and King Lear, as in the bursting of Joy’s grape, men enduring their going hence as their coming hither, etc. “How will we recall the ripeness when it’s over?” Is McCulloch’s plaintive phrasing of the theme, but since this song has already burst its skin one might almost read it as a lament for the loss of the group’s own ripeness.

‘Higher Hell’, ‘Gods Will Be Gods’, and ‘In Bluer Skies’ drift yet further into a subliminal state of suspension whose every measure has already been worn to the bone (“bones will be bones” , goes ‘Gods’). “Just like my lower heaven, you know so well my higher hell” . Here it’s all but confessed that what was once their heaven has turned into a hellish mire of their own making, the damnation of a style from which they cannot break free. They can only struggle from side to side, wearing away what was once a perfectly fit abode for their sound.

Porcupine takes the Bunnymen as far as beyond the Doors-meet-Television happy death pop of ‘Crocodiles’ as is either conceivable or desirable. It makes ‘All That Jazz’ and ‘Villiers Terrace’ look like nursery rhymes. I wonder if they’ll ever again write such a formidable youth song as ‘Pride’: that marvellous probing of the rock quartet’s limits, that rich, vigorous economy, all that may have gone for good.

Did they perhaps always mistake their hell for a heaven, or is this album, originally titled “Higher Hell”, the conscious obverse of Heaven Up Here? Are their deaths too high or did they aim too low?

Porcupine groans behind bars, an animal trapped by its own defences. Where the Banshees, always in danger of the same stagnation, can still amaze with a ‘Cocoon’ or a ‘Slowdive’, Echo And The Bunnymen are stuck in their grooves, polarised between ‘Pornography’ and ‘Movement’. They must haul themselves out. Instead of panicking at the approach of doubt they must celebrate it. To Mac must I say, as was said to the Duchess herself, “End your groan and come away.”

JC adds…….

It’s fair enough to argue that Porcupine is a lesser album than Crocodiles or Heaven Up Here, but this is a ridiculous hatchet job from the then 23-year-old Barney Hoskyns whose career as a music writer was beginning to take off. Would you be surprised to hear that he entered the profession on the back of a first-class honours degree in English from Oxford University? He certainly uses enough big words and the confidence in his views and opinions ooze from each barbed paragraph.

It’s another example of the music press turning on a former darling(s) for having the cheek to seek out mainstream success by penning hit singles and bringing in a new producer to add a bit of pop sprinkle to the sound. The band did have the last laugh, with Porcupine hitting #2 in the charts (still their best success in that regard), and spawning two top 20 hit singles, as well as laying the foundations for the release of Never Stop, a non-album single which also went Top 20. Oh, and the NME in its critics poll at the end of the year had it the album at #32….I’m assuming Mr Hoskyns had his dissent recorded in the minutes of the meeting.

My own reaction back in 1983 was that Porcupine was a bit of a strange beast. The Cutter and The Back of Love remain two of the most definitive songs from the whole decade by any singer or band, but other than Heads Will Roll (and perhaps Clay to a lesser extent) none of the other eight tracks on the album are really anything like them. That’s not to say that they felt truly disappointing or second-rate, but the difficulty is that the quality of the songs on the first two albums had been so high that, even with a two-year gap since Heaven Up Here, it was going to be very tough to keep such high standards.

I could go on, dissecting the review on a line-by-line basis, but I’ll leave it there, taking comfort in the knowledge that the ‘build ’em up, knock ’em down culture’ on show here has always been part of the cultural landscape in the UK and often is a knee-jerk reaction from snobs who hate commercial success.

I picked up a second-hand copy of Porcupine a few months ago – it was an album that a flatmate had bought on the day of its release and I never got round to buying my own copy, although it would become an early CD purchase in later years. These are from the vinyl:-

mp3: Echo & The Bunnymen – Clay

mp3: Echo & The Bunnymen – Gods Will Be Gods

mp3: Echo & The Bunnymen – Heads Will Roll

mp3: Echo & The Bunnymen – In Bluer Skies

The thing is, having got the vinyl and given it a spin, I found myself actually enjoying the album much more than I did back in 1983…..but then again, that was a year when The Smiths, Aztec Camera, Orange Juice, Altered Images, Elvis Costello & The Attractions, The Style Council, The Go-Betweens, New Order, The Cure Billy Bragg, PiL, The The, Cocteau Twins, The Fall and Paul Haig, to name but a few, released immense singles and/or albums, so it was a crowded market with very few records on repeated play…especially in a shared flat!

“… the fervour that has so often bristled this reviewer’s quills.” What a tool. Porcupine was a great listen when it came out and always has been.

Wouldn’t you love Hosktns’ view of this review now? A tool indeed Porcupine was the first Bunnymen album I actually paid money for (rather than having a cassette copy of) and continues o delight today.

Having just read Louis Wener’s autobiography, Its different for Girls ( can heartily recommend it whatever your feelings about Britpop and Sleeper are ) and her experiences if male music journalists – this review just reiterates why I really dislike most of the writers of the at the time big 3 . Much better reviews in Smash Hits !

By coincidence I played the vinyl a couple of times a month ago, – working from home during lockdown means I’m spending most of the day in the room with my record player, so to brighten up the gaps between zoom calls I’ve been playing LP’s I don’t have on CD or digitally, which probably best sums up what was my view of the album. And whilst it was good to listen to the Bunnymen again, it didn’t hit the heights of the first 2 albums, which I think reflects how great they are rather then how poor Porcupine is, its a very good album, which would probably be held in higher esteem if it was by another band of the era.

When Heaven Up Here came out, Hoskyns wrote, what I think is one of the most insightful features on Echo And The Bunnymen and the album in NME. It may have put him on the map, it did for me. So when this review came out, and yes I do have this in my archive of “Bunnym-emorabilia,” I remember being completely unnerved. Hatchet job is exactly what this was JC.

Porcupine is The Bunnymen difficult album. But I argue that is not a bad thing. As a 19 year old, I was quite prepared for the darkness of the album. We all know now how much friction and troubles existed within the band unit at this time, and the pressures to produce. This informed the album, certainly, but as an unaware fan, the songs on Porcupine raw and emotional. Ripeness, for me is classic Bunnymen, psychedelic Post Punk, like a continuation on from Villiers Terrace. My White Devil is one of my favorite McCulloch vocal performances.

Hoskyns betrays his own expectations over the actual art created by EATB on Porcupine. He falls foul of the oldest of music critic cliches – enjoying his own words more that the thoughts he is writing.

I don’t remember any of my fellow Bunnyfans at the time complaining about Porcupine, but I do remember it being their best charting album at the time, even in the US.

I took a while to warm to this when I bought it in the week of its release. Then I saw a live show on the 83 tour and realised these songs were immense. Heaven Up Here was great, but I’d argue that Porcupine, all dense textures and arcane lyrics, has aged better. For me, it was their peak and it was downhill from here.

Last time I played it, I was struggling to work out why my memory of it was slightly negative. Perhaps it’s only seeing the album in the context of the later, bland material that Porcupine can be fully appreciated. I may also have been influenced by the contemporary live shows which unquestionably didn’t reach the heights of the HeavenUp Here era shows.

Think even 20 year old me could spot a hatchet job this blatant (Steve Sutherland did something similar on Heaven Up Here in MM.)